Those contracted agencies do everything from manufacturing to chemical work to web and app development.

The pandemic was great for us because more people were at home. Many built pools and spent time in their backyards. So our direct-to-consumer sales have been solid over the last two years. To find prospects, we use datasets from Multiple Listing Services of Realtors. We know where people with pools live because we can see a house with a swimming pool that’s been sold.

Bandholz: I see so many opportunities for your business. Folks in Flint, Michigan, could have used it, for example, to detect lead levels in their water. Even here in Austin, residents have had water boil notices.

Bandholz: How do you manage such an extended team?

Kurani: Yes, that’s what we recommend. The device’s algorithm learns over time how your water chemistry changes. Bandholz: What’s keeping you awake at night?

The 85% shop online or go to a pool store to get their water tested. We want Sutro to be the Fitbit for your pool — an alarm that tells you if anything is wrong. The Sutro platform allows pool stores to see their customers’ data. Customers can then go to the stores and buy the chemicals. We hope to launch the platform this year.

Kurani: Having a project manager is critical. That’s someone who knows everything across the organization, more or less a chief operating officer.

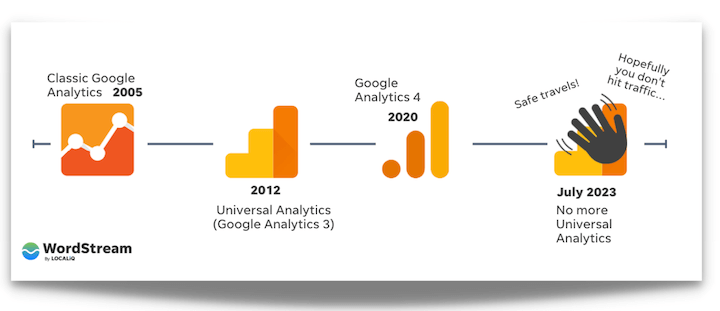

Ramping up sales keeps me awake, too. We’ve done a lot of advertising for brand building. Our ratio of customer acquisition cost to lifetime value is higher than usual. I want to bring that down for profitability. The Facebook algorithm change last year hit us hard.

Kurani: Yes, that’s correct. I used to be an associate at a venture capital fund in India. The fund’s primary purpose was to invest in companies focused on technologies and products for folks who make less than a day. Poverty is a big concern in India. Lack of food and clean drinking water is a huge problem there.

Much of our deal flow was around drinking water filtration, but nobody was looking at water sensing. Those devices cost upwards of ,000 back in 2011. There were very few companies that did water sensing. So we built our first water sensor in India around 2012. We tried selling it to the Indian government. It was the stupidest idea ever. Don’t try to sell anything to a government. It takes forever.

Bandholz: You’ve shifted Sutro to focus on pools and spas. How do you sell your devices?

We’re not knocking on every pool store’s door. We’re working with chemical companies to help them use the Sutro technology to better instruct the pool stores and their customers on what to put in a pool. That’s our model.

Kurani: No. We were venture-capital-backed for the first five years. In 2017, Sani Marc, a large chemical company in Canada, acquired us. I now run that subsidiary.

Bandholz: Tell us about your staff.

Bandholz: Are you still VC-backed?

Kurani’s solution was to return to California, his home, and pivot the company. Its sensor would target swimming pool owners, not drinking water providers.

But the better way is to sell to municipalities. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires city governments to test their water. But that would involve selling to a governmental entity, which was our first problem in India.

Ravi Kurani is an engineer and former venture capitalist who launched Sutro, a water sensor manufacturer, in 2012 in India. The company produced devices that measured drinking water quality, a major concern there.

Kurani: We launched our first device for that market during the pandemic. Everything we planned for distribution and retail sales changed. We quickly adjusted to more of an online presence.

He recently described his journey to me. Our entire audio conversation is embedded below. The transcript is edited for clarity and length.

Kurani: Yes. We could distribute to that segment in a couple of ways. We could sell directly to individuals. They could attach our product to their tap and measure the water in real-time.

Customers do not have to understand or program levels of pH, chlorine, and more. Our system is self-defined. It knows all the complex chemistry and mathematics to get you to that right level. We consider many variables, such as the local weather in Austin or your starting water chemistry.

He told me, “We tried selling to the Indian government. It was the stupidest idea ever. Don’t try to sell anything to a government. It takes forever.”

Our system tells you exactly what chemicals to add. Our robot does not yet put the chemicals in the water, although that feature is coming.

The pivot worked. Sutro is now thriving as a direct-to-consumer seller and a technology firm to chemical companies and pool suppliers.

Bandholz: Your device wasn’t initially for swimming pools and spas.

Bandholz: Are you an engineer?

Kurani: Supply chain issues. We can get products made in China, but getting them to the U.S. is a problem. There’s a shortage of shipping containers. Many ports are clogged or blocked.

That, in a nutshell, is what we do.

Bandholz: How do you develop relationships with the pool stores?

Kurani: Yes. My background is in mechanical engineering, with a minor in fluidics — the use of fluids to perform analog or digital functions. I worked at NASA for about a year after college. And then I got an MBA and worked in the venture capital industry. A lot of the technology in our initial sensor is from my mechanical engineering and fluidics days.

Kurani: We’re up to about 50 team members. The core group is just seven people. The others are mostly contractors in China that do our manufacturing. We have a small group in Quebec at Sani Marc, our acquirer, doing the chemistry and lab work. Our web and app development team is primarily in Kosovo, north of Greece, with a few in Mexico City.

Lastly, we make sure that Slack is a safe space. Engineers, especially, are often shy about communicating on Slack. We want a culture where people can talk about anything on that app. We have face-to-face communication on Google Meet. But Slack is our place for daily dialog and conversations.

We’re still interested in eventually solving drinking water problems. Anywhere water purity is an issue, we want to be there.

Kurani: Our website is MySutro.com. We’re selling our devices right now. Hit the buy button, and you’ll have a Sutro in your house in three to five days. I’m on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Eric Bandholz: Give us a rundown of Sutro.

I came back to California. My dad and mom once owned a chain of pool and spa supply stores. We flipped the business model around. Rather than focusing on poverty, we decided to sell the sensor to wealthier communities, to folks that own swimming pools and spas.

Bandholz: Does your robot stay in the water 24/7?

We aggregate that data and then plug it into Facebook and Google for ad campaigns. We also have retargeting campaigns similar to typical ecommerce businesses.

Bandholz: Where can folks reach out to you and buy your products?

We split the organization in terms of products, such as manufacturing, app development, and web development.

We’re now building a platform for pool stores to interface and communicate with their customers. Eighty-five percent of pool owners monitor water quality themselves.

Kurani: Sutro is the middleman. We recommend chemicals. We work with chemical companies to ensure that we’re right-sizing their product for pool owners. That’s how we get into pool stores.

Ravi Kurani: Sutro is a floating robot that ensures your swimming pool and spa water are safe. It’s a small laboratory that detects your pH level, chlorine, alkalinity — all in a simple app — so you know what chemicals to add and when. If you don’t have those chemicals, we connect you to a local pool store to purchase.

![Social Media Has Outgrown the Walled Garden [Here’s Why]](https://research-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/what-to-know-before-you-sell-your-small-business-768x432.png)

![[Infographic] Expert Opinion Round-Up: What Does GDPR Mean for Marketers?](https://research-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/infographic-expert-opinion-round-up-what-does-gdpr-mean-for-marketers-768x576.jpg)