DTC and CPG brands and retailers should treat essential and non-essential products differently, perhaps raising prices to match expenses in the former and finding alternative ways to combat inflation in the latter.

Not long ago, a supermarket sold a four-pack of egg substitute for .99. Then it was .79. And then it was .49.

But retailers might want to up their house-brand game, adding new private label products at lower price points than the brand-named goods they already sell.

A direct-to-consumer or consumer-packaged-good brand impacted by such behavior could garner more short-term sales but face longer-term challenges in inventory availability and shopper behavior.

Jeff intends to stay on budget despite everything becoming more expensive.

Essential products typically experience a much lower price elasticity than non-essentials. Folks keep buying essential goods even as prices soar.

Binge buying should be familiar to anyone who needed toilet paper in the summer of 2020.

Essential vs. Non-essential

There are many product categories that shoppers unanimously consider essential, such as food, basic clothing, and basic toiletries. Some shoppers will add personal essentials or near-essentials. For example, someone struggling with hair loss might consider Rogaine scalp treatment essential.

Let’s cite “Jeff,” who lives in New Hampshire. He canceled most of his streaming services in February as part of his inflation-fighting plan. He reduced household expenditures, trusted the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank to keep interest rates in line, and doubled down on his investing.

For this type of shopper, the cost-cutting may start with subscription services. You can’t watch Netflix, Hulu, and HBO Max simultaneously. So why have all three? He may also cancel his monthly box of curated fashion clothing and the regular delivery of dog toys.

Hence an inflationary market can be good for low-cost private label brands and not so good for premium items. Brands and stores alike should consider this as they contemplate prices increases, positioning, and promotion.

Some shoppers, facing rising prices, may opt to reduce overall spending.

Quantity over Quality

In short, inflationary buying behaviors force retailers and brands to consider the positioning of their products and plan for changes in demand.

This might be especially true for DTC brands with premium-priced products. They may need to reposition to retain customers against low-cost competitors.

If his usual egg substitute is out of stock, a consumer might try a substitute for his substitute.

Shoppers might opt to stock up as buying power wanes. A consumer of egg substitutes who believes the price will keep rising may decide to toss a few extra boxes in the freezer before the price jumps again.

As prices rise for goods and services, shoppers have less buying power and may change buying habits.

This behavior can create a demand flywheel, increasing inflation. It also tends to disrupt the supply chain. It could even commoditize some products. If his usual egg substitute is out of stock, a consumer might try a substitute for his substitute.

Buy Less Overall

Jeff views rising prices as an opportunity to remove financial clutter and buckle down on expenses

But some businesses may not know if their products are essential until sales have jumped or slumped.

Amid inflation, shoppers may seek the same sorts of products but at a relatively lower price. These folks are looking for quantity over quality.

When inflation is low and finances are good, many shoppers prefer premium goods.

For some buyers, inflation might result in prioritization.

His actions impact DTC and CPG brands alike.

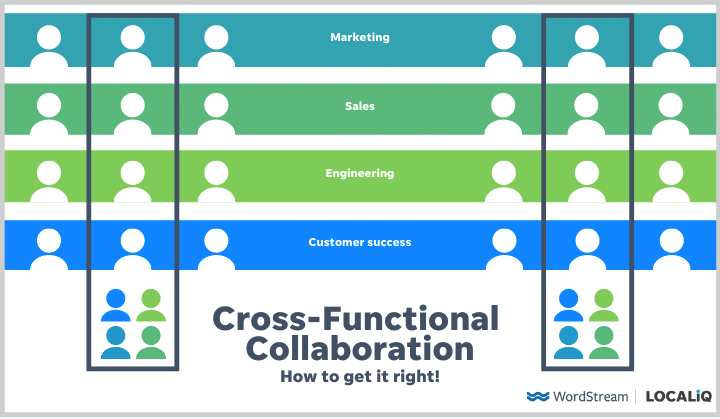

Knowing the Market

A consumer who buys premium coffee beans when prices are low could become a fan of an inexpensive store brand if the cost rises.