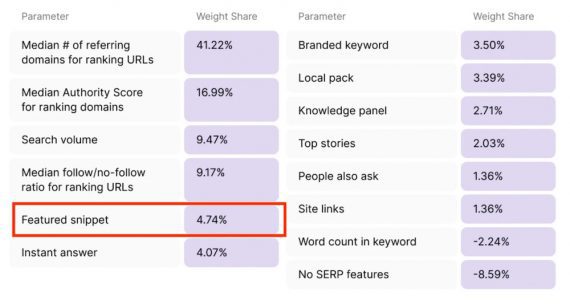

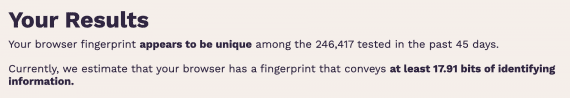

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, which promotes privacy online, has its own browser fingerprinting test called “Cover Your Tracks.” A recent test on Cover Your Track shows that about 18 pieces of information from a browser made it possible to identify me from a pool of 246,417 tests conducted for a 45-day period.

Privacy advocates, tech companies, and government regulators are all working to bring an end to third-party cookies. But even as the cookies crumble, some ad networks could turn to browser fingerprinting to track individuals.

Browser Fingerprinting

As the name implies, browser fingerprinting is similar in concept to actual fingerprinting. When the police fingerprint a suspect, they compare that fingerprint to a database of previously collected prints. When two prints match, they are assumed to be the same person.

These researchers analyzed the 100,000 most popular websites based on Alexa rankings. Of these, their fingerprint tracker found that more than 10,000 or approximately 10 percent (25 percent of the top 10,000) were fingerprinting visitors.

It is not unreasonable to think that advertising networks could increase the use of browser fingerprinting as tracking cookies become less available.

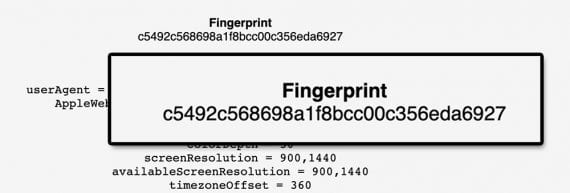

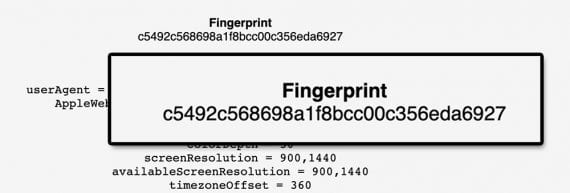

Rob Braxman, an online privacy advocate, has a browser fingerprinting tool that will produce a hash or value representing you. On Braxman’s tool, this value is labeled “Fingerprint.” If you visit the tool in Chrome, for example, then close the browser and reopen it, you will notice an identical fingerprint. The tool knows who you are without the aid of a cookie.

Cookies are one of the easiest ways for advertising networks to track individuals. When a publisher puts ads on its site, the ad network places a cookie on each new visitor’s device. When that same visitor goes to another website using the same ad network, the cookie is recognized, and the individual is tracked. The cookie is placed by a third party (the ad network) and not the publisher. Thus, it’s a third-party cookie, also called a tracking cookie.

- The browser you’re using (e.g., Chrome, Safari, Firefox),

- The language (e.g., English, Spanish) your system is set to,

- Color depth,

- Screen resolution

- Time zone,

- Platform (e.g., Windows, Mac),

- WebGL settings,

- Storage settings,

- Plugins.

Now that they know how invasive and secretive browser fingerprinting is, these advertisers can decide if they are comfortable buying ads on networks that employ it.

Fingerprinting Is Easy

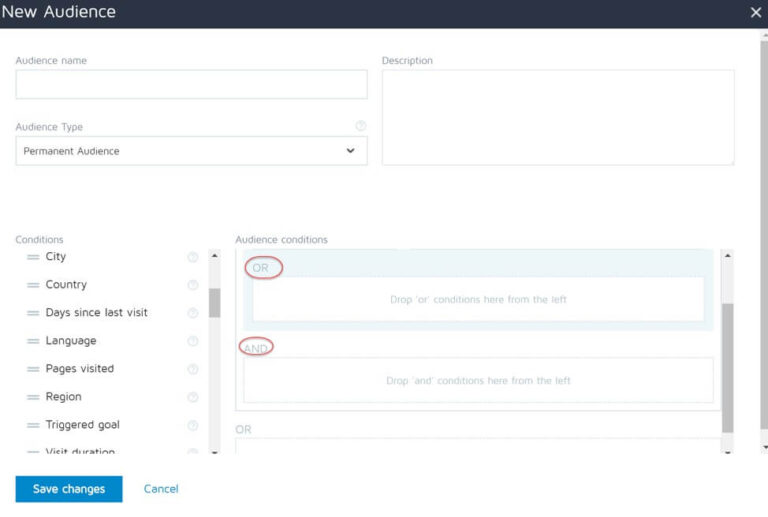

Privacy expert Rob Braxman was able to identify a browser and, by association, its user via a fingerprint.

When several of these points of information match, an advertising network knows with a pretty high degree of certainty that it has the same individual in view.

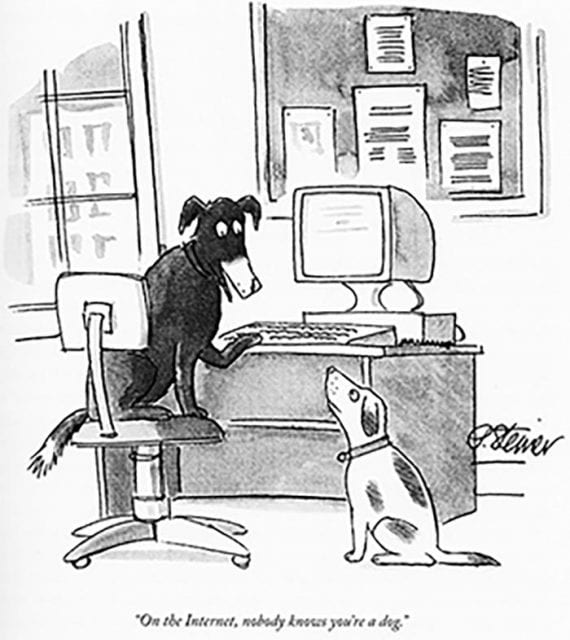

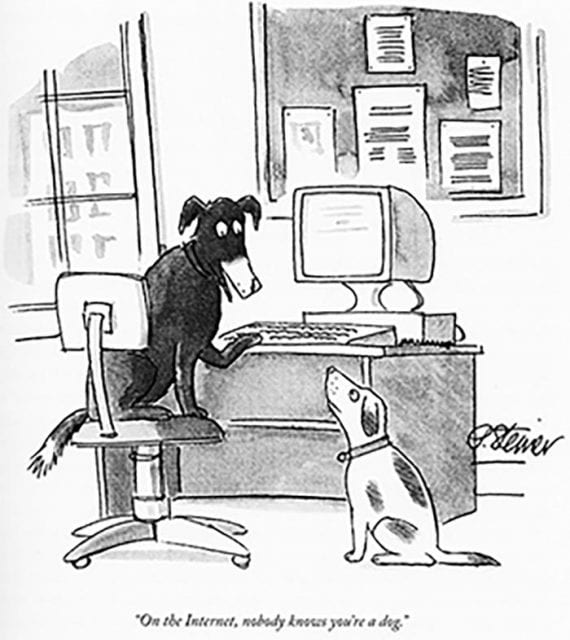

In 1993, cartoonist Peter Steiner saw the internet as a place of anonymity, but that has clearly changed. Source: Wikipedia.

As common as they are, tracking cookies are not the only way ad networks follow folks. For many years, lots of ad networks have also used browser fingerprinting.

Fingerprinting Is Common

When you visit a website, your browser shares information about itself and your device. This information includes things like:

Facebook and Google, which are among the largest ad networks, do this at scale.

“Fingerprinting the Fingerprinters: Learning to Detect Browser Fingerprinting Behaviors,” a paper prepared for the IEEE’s 2021 Symposium on Security & Privacy, described how researchers Umar Iqbal from the University of Iowa, Steven Englehardt from the Mozilla Corporation, and Zubair Shafiq from the University of California, Davis were able to detect browser fingerprinting.

Browser fingerprinting is not new and not obscure.

“In July 1993, The New Yorker published a cartoon by Peter Steiner that depicted a Labrador retriever sitting on a chair in front of a computer, paw on the keyboard, as he turns to his beagle companion and says, ‘On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.’ Two decades later, interested parties not only know you’re a dog, but they also have a pretty good idea of the color of your fur, how often you visit the vet, and what your favorite doggy treat is,” wrote Nick Nikiforakis and Günes Acar in a July 2014 article for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Spectrum magazine.

Commerce Advertisers

Cover Your Tracks identified 18 pieces of data that identified the author out of 245,417 possibilities.

Educating advertisers is a side effect of the personal privacy movement.